In November I wrote on Instagram that I was on my way out of a tunnel of severe anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation. It was a triumph for me to say that and also a rebellion against the assumption that because I am in possession of good things, I am in isolation from a screaming world.

It took me by surprise that I also quickly felt a need to protect myself against being misunderstood (alas, not always within my powers). I’ve had some time to weigh my defensiveness, and I want to frame my experience within a larger picture.

On Monday (2/26/24) a man named Aaron Bushnell, an active-duty airman about to be deployed to Israel, lit himself on fire in protest of the US’ complicity in the genocide of Palestinians. He died of his wounds.

I heard that Bushnell’s sanity was quickly questioned by panels of bobble heads. The writer Hanif Abdurraqib (@nifmuhammad) shared a series of thoughts in his Instagram stories that I screenshot and transcribed that draw1 a picture of our social understanding of mental health, protest, and death by suicide.

Abdurraqib referenced the abolitionist John Brown (1800-1859) whose friends urged him to plead insanity to avoid the death penalty during his trial for treason (he occupied a US military arms depot while leading a revolt of enslaved people), but Brown refused, maintaining that he acted with clarity of conviction. Abdurraqib writes2:

…As if living with and engaging with the world through a lens of mental health struggles means a person cannot also have firm and fierce political convictions, willing and more than capable of making choices in the name of those convictions. People with myriad mental health conditions are aligned in struggle alongside and for you, are on the frontlines somewhere, have decided on their own, with clarity, what to fight for and how they can and will do it.

Most everyone is living in a state of crisis, some are just more honest about it than others. If you are someone who can make yourself oblivious, that is a different kind of unwellness. Accessing care for mental health in a time of life and death crisis is near impossible [for myself] and also for incarcerated or formerly incarcerated people. This is a country that enjoys using the broad specter of “mental health” to both escape accountability and avoid any self-reflection while also doing nothing to address the very real crisis in mental health accessibility, which suggests to me that there is an intentional incentive to that lack of addressing the issues of care and access.

I have loved people who made an active decision to not be here anymore and struggle with the realities of being here myself, and in my experiences, these were decisions governed by dissatisfaction with a world that had become impossible to live in, a world so far from being a caring place that it is untenable, impossible to survive. To dismiss those conditions and assume that “mental health,” in the broadest sense, removed any clarity or purpose or autonomy, flies over [reality].

Perhaps founding a nation on genocide and then enslaving people during that nation’s foundational era creates the seeds of a deeply sick society that simply cannot and will not get exponentially better, and so it doesn’t feel like it is my place to have an overwhelming investment in declaring “sanity” (defined by the state) of anyone acting in opposition to unjust manifestations of this nation’s sickness, regardless of the tactic. In my younger years I have, quite frankly, wanted to die for much, much less.

I find it strange and painful that we demand that people defend their own suffering. As if to say, What right do you have to break when crushed?

There is a category into which I will boldly place myself and others where I can experience both illness and an appropriately mirrored response to my surroundings. Feeling the reality of my surroundings is not a symptom of illness, even if I am ill in concurrence with specter of death all around.

Last fall, I could feel the chemical warfare in my brain and nervous system. I felt very sick and as much as I was able to formulate a wish, I wished for anything that might make me feel not sick. It seemed to me that there would be little difference in waking versus not waking, and perhaps not waking would be marginally more peaceful.

I didn’t know what intrusive thoughts were until recently. At that time, most of my thoughts were intrusive, wildly violent and violently persistent. Mostly I sense that I should not voice them because they are scary and will scare other people. People will think I’m crazy. And yet they are adjacent to memories.

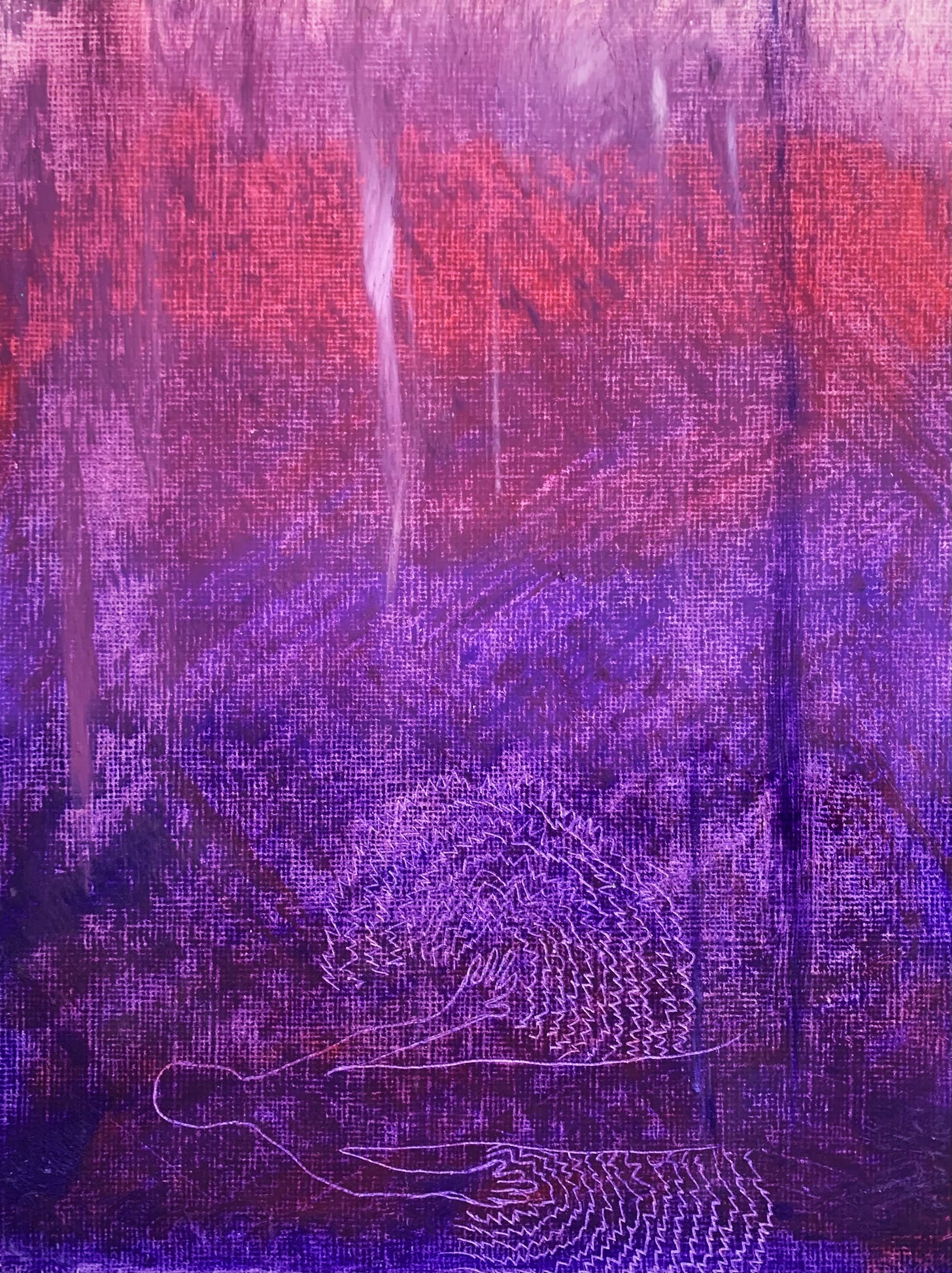

“In my dream, I couldn’t stop shaking.”3

In the midst of being sick, I was defending my knowledge and experience of reality. Public shootings, murders, assaults, abuses, injustices, hunger. Not only on the global and systemic scale, but in my own life and the lives of my friends and family and communities.

I’m not a reporter nor is my aim to trauma dump through my writing. But perhaps people mistake my generalized statements as intrusive concerns, when in fact I know people, by name, who do not have adequate food. I have a story, with a face to it, for every item on that horror list above. Nothing seems more urgent to me than to fill those bellies, dress those wounds.

When I partake of the flowers of the field, I often experience about 10 minutes of what I’ve come to think of as toxin release. It hurts. My whole body aches and I envision all the pain I’m holding bubbling up through my bones and blood and muscles until it’s exiting my skin like vapor, or like a ghost released.

A new heart also will I give you, and a new spirit will I put within you: and I will take away the stony heart out of your body, and I will give you a heart of flesh.4

I wanted to get better, but also I want the world to get better. I feel grieved when I express that and the connection seems mysterious to some. I want my loved ones to be rescued. I want strangers to be rescued. Forgive me my tantrums when there is concern for me in my illness and a blank stare about the causes of illness.

Learning about mental health can be overwhelming because I start to feel like nothing more than the inevitable product of my environment. A watery concoction of trauma responses with some floating bits of me. It’s weird that that’s exactly what I am - a product of my environments - and the environment turns to me as one and says, “take this pill, you sick person.” (On the other hand, it would be nice to be able to drive to dinner without using the entire power of my brain to suppress the idea that another driver might shoot me in the head.)

Our nervous systems play these movies to protect us. My intuition is not unfounded. Anxiety is not just self-fulfilling prophecies, it’s seeing patterns and knowing what suffering does inside of people. Inside of me. I don’t want to succumb to my own chemicals. I also don’t want to be lulled to sleep while the world burns, hushed by the song that it’s not real fire.

I am reminded that not everyone experiences life this way. Most of us are navigating crises in one way or another, but not everyone manifests the denial of the connection between personal and global struggle as a mental health emergency. In fact, I hope that my children can see destruction and lack of love with clear eyes and not take it personally. I wish for them nervous systems that absorb the good and release the bad. I hope they escape mental illness and also recognize people with mental illnesses in our capacity as seers.

Last month I wrote about a movie depicting a true story in which a group of people in a dire situation decided it was less ethical to allow themselves to die by starvation than it was to consume the bodies of their deceased friends in order to live. Mostly, their sanity was not questioned in the midst of their extreme circumstances. They reasoned that if there was any way to preserve their lives without hurting each other, they should do so.

Sanity is something we think of as having absolute parameters, and yet it is very informed by our culture and time. Aaron Bushnell may or may not have had “mental illnesses” but he definitely sacrificed his own life with clarity and intention for the sake of others. There is an ancient tradition that teaches there is no greater love than to sacrifice oneself for the sake of others5.

When I was thinking about Bushnell’s sacrifice, I was reminded of Jesus. Jesus didn’t die by his own hand, but he also didn’t take the opportunity to escape death when he could have. He did not preserve his own life at all costs. Instead his acceptance of his death was a beacon shown on his hope that the ones he loved might live6.

By current social standards, Jesus was not sane. I recently saw a stand-up clip of a comedian mentioning how an outsized number of people in mental institutions claim to be Jesus. He said that if a person goes around saying they are Jesus, they are likely to be put into an institution with the other Jesuses. His joke was that Jesus might be coming back repeatedly only to be institutionalized.

Mostly I’ve believed that symbolically, but it is actually true in a way that I’m sometimes very uncomfortable with. There’s a pervasive idea that we’re “safer” by crossing the street away from the stumbling crazy person. But who is really stumbling crazily away from the reality of Jesus in that scenario? Mental illness or “crazyness” is often used to dismiss what someone else is seeing or feeling or experiencing that we do not want to be real. In fact, we often punish people for acting on their convictions.

When Aaron Bushnell was engulfed in flames, one security guard was hosing him down with a fire extinguisher and calling for help. Meanwhile, a police officer was pointing a gun at Bushnell. How familiar this scene, played out in so many ways, across so many years. Remember the guards below Jesus’ dying body, playing dice and poking his side with a spear? To them it was another day on the job. Another nut job claiming to be Messiah, perhaps even a menace, with whom the law caught up.

When people choose to die by their own hand, or express a desire to slip away from this life, some well intentioned folks are quick to remind us that our lives are not our own. In all the most confounding ways, that is true. We come into this life through no choice of our own, and none of us make it out alive. In-between, we are wrapped up by love and by war, by the evil and the good. We are connected to one another in ways we cannot entirely control, and through those connections we become complicit. Complicit in love, complicit in hatred.

Like Bushnell, I’ve felt that the only way I can disconnect myself from involvement in any form of harming others is to remove myself from the equation. Suicidal ideation is not the same thing as wanting to die. Death itself is far lesser an enemy than another person imposing death on you. Or on others in your name. I don’t know if Bushnell wanted to die so much as he wanted to stop the murder of others. Death, including suicide, does not exist without touching other people. And maybe that was the point.

Instead of choosing my own death, I’m still trying every day to work against the wildfire of harm that threatens to engulf every last one of us. But never will I fault a body for “wanting to die for much, much less.” I honor the sacrifice of those who succumb to their suffering, who lay down their lives for love, by paying attention to their message. By taking up the fights they sacrificed their lives for. Not to “give their death meaning” (a misguided quest on our part) but so that we may live7.

He saith unto him the third time, “Simon, son of Jonas, lovest thou me?” Peter was grieved because he said unto him the third time, “Lovest thou me?” And he said unto him, “Lord, thou knowest all things; thou knowest that I love thee.” Jesus saith unto him, “Feed my sheep.”8

Whenever I express a desire to fly away, I invite you to fight alongside me. That makes me feel cared for, it is good medicine for my mental illness.

I like that words like “draw”, “weave”, “paint”, and “shape” are how our language describes the connection between ideas.

Edited by me for relative brevity, and without permission, I ask forgiveness in the future if necessary.

“In my dream, I couldn’t stop shaking.” 2023, Oil pastel. This drawing is part of a series I may or may not finish that illustrates parts of my mental health experience at the time.

Ezekiel 36:26

John 15:13

2 Corinthians 5:15

One Instagram account I love is called @asafeplaceinsideyourhead and it was created by a family whose son died by suicide.

John 21:17. I chose this older translation because I like the word “grieved.” See also John 13:34 and and John 14:15.